15 Apr How to calculate your innovation’s odds of success

When I first became a CEO, at age 33, I read everything I could find about legendary business leaders and the companies they created. I was trying to discover the secret to building an innovative organization that would empower employees, deliver on our bold mission to develop a new cancer drug, and reward stakeholders. The answer, according to many, was corporate culture:

“The good thing about [our] culture is that nine times out of 10, people are going to say, ‘Hey, let’s try it. Let’s see where it goes.”

“You’re allowed to have a bit of fun, to think unlike the norm…to make a mistake.”

“We’ve been able to build such a strong brand and global presence…because we really built…an amazing culture.”

Unfortunately, those quotes came from the CEOs of GE, Nokia, and RIM (BlackBerry) shortly before the market value of their firms plummeted, collectively, by half a trillion dollars. The companies were exploratory, “fun,” tolerant of mistakes, and capable of fostering groundbreaking work—until they weren’t.

Management theories that focus on culture have always felt squishy to me. As a physicist, I was looking for some harder science. How could these companies so quickly shift from nurturing “crazy” projects—the “loonshots” that transform industries—to rejecting important innovations? Why would good teams, with excellent people and the best intentions, kill great ideas? It reminded me of what scientists call a phase transition: a sudden change in the collective behavior of the many interacting parts of a system. In the case of water, for example, the shift happens at 32 degrees Fahrenheit; the molecules stop roaming freely (liquid) and instead lock rigidly in place (ice). Over the past decade, scientists have applied this principle to help us understand how birds flock, brains work, people vote, traffic flows, markets behave, ideas spread, diseases erupt, and ecosystems collapse. Over the past few years, I’ve built a model that applies phase-transition science to help us understand how organizations change.

The model draws on my experience in different workplaces (from a global consulting firm to a two-person start-up that grew into a publicly traded company) along with research into other organizations. It shows that there is a certain size at which human groups shift from embracing radical ideas to quashing them. Let’s call this the magic number M.

The model shows us more: This transition point is not fixed. It is a function of two competing forces, the relative strength of which can be adjusted through variables we call control parameters. In water, this tug-of-war is between binding forces (which favor rigidity) and entropy (which favors sloshing around). The system usually snaps at 32 degrees, but when you introduce another element, such as salt, the freezing point shifts to a lower temperature. In organizations, the competing forces can be described as “stake in outcome” versus “perks of rank.” When employees feel they have more to gain from the group’s collective output, that’s where they invest their energy. When they feel their greatest rewards come from moving up the corporate ladder, they stop taking chances on risky new ideas whose failure could harm their careers.

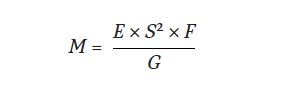

Leaders can tip the balance and raise the value of M—ensuring that radical innovation continues in even the largest company—by tweaking four key control parameters. They are equity fraction ( E), fitness ratio ( F), management span ( S), and salary growth ( G). Note that none of these are elements of “culture.” They are better described as elements of structure: organization design. As the equation below illustrates, a higher M results from increasing E, S, and F (the parameters in the numerator), and decreasing G (the denominator).

Let’s look at how the four parameters work in practice.

The Four Control Parameters

Imagine that you’re a designer at a medical device company, and your job is to develop a better pacemaker. It’s 4 pm, and you need to decide how you’ll spend the final hour of the workday. Should you experiment a little more with your design, or should you use the time to network, currying favor with your boss or other influential managers? In other words, should you focus on project work or on politics?

Such daily choices, faced by pacemaker designers and midlevel workers of all kinds, are what really determine the level of innovation at a company—not cultural changes instituted from the top. Loonshots, the building blocks of innovation, are fragile and need broad support; one table-pounding champion cannot take an idea to market. Prototypes must be designed and built, market segments need to be identified, field tests need to be conducted, and so on. In order for “crazy” ideas to turn into successful products, people across the organization need to be incentivized to invest their time in moving projects—not themselves—forward.

Here’s how each control parameter affects behavior:

Equity fraction.

This variable represents the extent to which incentives reflect the outcome of projects as opposed to rank within the organization. Equity fraction ties your pay directly to the quality of your work. If you create a revolutionary pacemaker, the company will probably sell a lot of them, and the value of your equity will grow. Equity comes in two forms, hard and soft. Hard equity includes stock options, grants, commissions, bonuses, and so on. Investment funds pay portfolio managers a percentage of risk-adjusted returns, for example, and professional services firms compensate partners on the basis of the client revenues they bring in. The Chinese appliance maker Haier keeps base salaries low and pays its customer-facing small business units according to their customer sales.

Soft equity—nonfinancial stakes, such as peer recognition—counts, too. If your pacemaker design could be submitted for an industry award, you have a soft equity stake in the success of your project. At Wolfram Research, a computer language and data science company, CEO Stephen Wolfram raises the soft equity stakes by live-streaming programming sessions and development meetings with clients. This creates immediate visibility and accountability between engineers and their core customers.

Whether your equity stake is hard or soft, the higher the fraction, the more likely you are to spend that extra hour on project work rather than on politics.

Fitness ratio.

This parameter involves the relationship between project-skill fit (PSF) and return on politics (ROP): F= PSF/ROP. Economists would call this a ratio between two marginal returns. The numerator is a measure of the rewards from investing time in your project. The denominator is a measure of the rewards from investing in politics.

Suppose you are a highly skilled medical-device designer. An extra hour per day invested in working on your pacemaker might double or triple its value; you might even create a design that will outsell every other one in the industry. The excellent fit between your skills and your project (high PSF) would tip you in favor of spending more time working on it. There would be no need for schmoozing; your triumph would speak for itself. Suppose, on the other hand, that you’re not well suited to the projects to which you’ve been assigned (a low PSF). Your design skills are lousy, and one more hour wouldn’t help much. You might as well invest that hour in politics; it might be the best or the only way for you to win a promotion.

In some cases, a poor project fit results from an undermatch: An employee’s skills and experience are not up to the task. But an overmatch—skills so far above project needs that the employee is contributing only a fraction of what he or she could offer—is also a problem. Imagine a young Elon Musk assigned to the pacemaker. The project wouldn’t offer much of a challenge, and he’d have plenty of time to start politicking. An organization achieves high project-skill fit when all its employees are stretched neither too much nor too little by their roles.

People need to be incentivized

to move their projects—not themselves

—forward.

Return on politics, the denominator in the fitness ratio, is a factor that every employee feels even though it is difficult to measure. It’s the extent to which lobbying, networking, and self-promoting affect promotion decisions. This will vary from team to team, but every company will have an average level. Consider two global manufacturers, Company A and Company B. Each has a California office with three vice presidents and 30 product designers. In both firms, a spot opens up for a fourth VP; one of the 30 designers will be selected. Company A is like most firms: The local office will decide who gets promoted. Throughout the decision-making process—which will take nearly a year—those 30 designers will compete to curry favor with the VPs. The return on politics is high. At Company B, however, an independent evaluator who has no ties to anyone in the California office will conduct an assessment and present the findings to an independent group of executives who will make the decision. Since there’s little benefit to lobbying, designers at Company B will be likely to focus on their projects and on collaborating well. The return on politics is much lower.

Management span.

Sometimes called span of control, this refers to the average number of direct reports that executives of the company have. The question of what the “best” management span is has been debated in the organizational literature for years. To see how this parameter affects innovation, imagine that you work at a 1,000-person company with an average management span of two. That means there are 10 levels in the hierarchy (the CEO has two direct reports; those two managers have two reports; those four managers each have two, and so on). When organizations have many layers—that is, a narrow span—promotions are on everyone’s mind, “tempting researchers to worry more about titles and status than problem solving,” as the internet pioneer Bob Taylor once noted. Now think of the same company with an average management span of 32. In this case, there’s only one management layer between the CEO and the people doing the real work. Promotions occur so rarely that no one thinks about them; instead they focus on their work. The large group of equal-level colleagues provides “a continuous form of peer review,” Taylor said. “Projects that are exciting and challenging obtain more than financial or administrative support; they receive help and participation from other…researchers. As a result, quality work flourishes; less interesting work tends to wither.”

Narrow spans aren’t inherently worse than wide ones. Narrow is better if you want low error rates and high operational excellence. Wider spans and looser controls are better for experimenting and developing loonshots and new technologies.

Salary growth.

The average step-up in base salary (and other executive perks) that employees receive as they ascend the hierarchy is another important factor. Again, envision yourself as the pacemaker designer and consider how salary growth might affect your decisions. If every promotion at your company comes with a whopping 200% increase in salary, you’d want to make sure that every influential person knows exactly who you are and why you and not your colleague down the hall should be promoted. If, however, promotions yield only a meager 2% pay raise, you might as well pour your energy into your project, where some extra effort could earn you a bigger bonus or increase the value of your stake in the company’s success. Low salary step-up rates encourage people to use the last hour of the day on work, not on politicking. Recent academic studies have come to a similar conclusion. One noted that “increased [wage] dispersion is associated with lower productivity, less cooperation, and increased turnover.”

Putting It All Together

There are many ways companies can adjust the control parameters to increase M and enhance innovation. Here are a few:

Celebrate results, not rank.

To increase the equity fraction and lower the salary growth rate, management must structure rewards to be based more on results than on level in the hierarchy. Most companies today do the opposite: Not only have base salary step-up rates been rising in the United States, bonus opportunities at junior levels are tiny or nonexistent (10% or less of base salary). Bonus fractions at senior levels, by contrast, can be upwards of 50%. Celebrating results rather than rank means changing compensation practices—and eliminating (or toning down) widely visible perks of rank such as luxury executive retreats, special cafeterias, favored parking spots, and so on.

Use soft equity.

Many studies have shown that different people are motivated by different things. To some, tangible financial rewards are most important. Others are driven by peer recognition or the desire to help others, or by intrinsic motivators such as a sense of accomplishment and personal growth. Companies should identify and use all the means at their disposal—nonfinancial in addition to financial—to increase employees’ stakes in the success of their projects.

Take politics out of the equation.

Employees need to see that lobbying for pay and promotions will not help them. One way to do this is to have those decisions depend less on an employee’s manager and more on impartial assessments by neutral parties. When promotions are considered at McKinsey, for example, a partner from a different office and preferably a different functional practice interviews candidates’ colleagues and clients and then reports back to a group of partners who make the decision. Google uses a similar process. As former HR chief Laszlo Block explains, new managers “are dumbfounded that they can’t unilaterally promote those whom they believe to be their best people.” The time and expense involved in creating such a system is significant, but it is a worthwhile investment in organizational fitness.

Invest in training.

Companies usually invest in training employees with the goal of better products or higher sales. Send a device designer to a technical workshop, and you’ll probably get better pacemakers. Send a salesperson to a speaking coach, and his pitch delivery might improve. But there’s another benefit: A designer who has learned new techniques will want to practice them. Training encourages employees to spend more time on projects, which reduces time spent on lobbying and networking.

Perfect employee placement.

Designate a person or a small central team to regularly scan the organization for project-skill fit, ensuring that everyone, from new hires to old-timers, is in the right job at the right time. The person or team making assignments should be separate from any particular function to ensure a broad view of the organization. The head of product development, for example, may not be the best person to judge whether a struggling device designer might actually make a great sales rep.

Fine-tune the spans.

Companies should widen management spans and design looser controls for groups in which radical innovation is the goal. Those structures encourage experimentation, peer-to-peer problem solving, and engagement in project work. Google’s former head of engineering, Bill Coughran, once had 180 direct reports.

Appoint a chief incentives officer.

Organizations need top-level executives who are well trained in the subtleties of aligning incentives and solely focused on achieving a state-of-the-art compensation system. A good incentives officer can identify wasteful bonuses (such as blanket stock options and bonuses based on companywide, rather than group or individual, performance), reduce the risks of perverse incentives (for example, when an auto dealer’s sales goals for service reps lead to overcharging customers), and tap thoughtfully into the power of nonfinancial rewards (peer recognition, choice of assignments, freedom to work on a passion project, and so on). The goal of achieving the most motivated employees for a given compensation budget is as important and strategic to companies as is the goal of achieving the best sales for a given marketing budget (the province of a chief revenue officer) or the best IT systems for a given technology budget (a chief information officer’s terrain).

CONCLUSION

We’ve all seen companies suddenly and mysteriously change. Innovative teams, widely praised for their breakthrough products and vision, begin rejecting the most radical ideas. The people are the same; the culture is the same—yet people suddenly stop taking chances. The bad news is that all organizations are susceptible to such phase transitions. The good news is that just as the freezing point of water can be lowered by introducing elements that favor entropy, key elements of an organization can be managed to foster more-innovative teams even as companies increase in size. Culture still matters, of course, but it’s time to pay a little more attention to structure.

A version of this article appeared in the March–April 2019 issue (pp.74–81) of Harvard Business Review.

Author: Safi Bahcall

HBR March–April 2019 Issue

Source: HBR